By Julia Schwarz

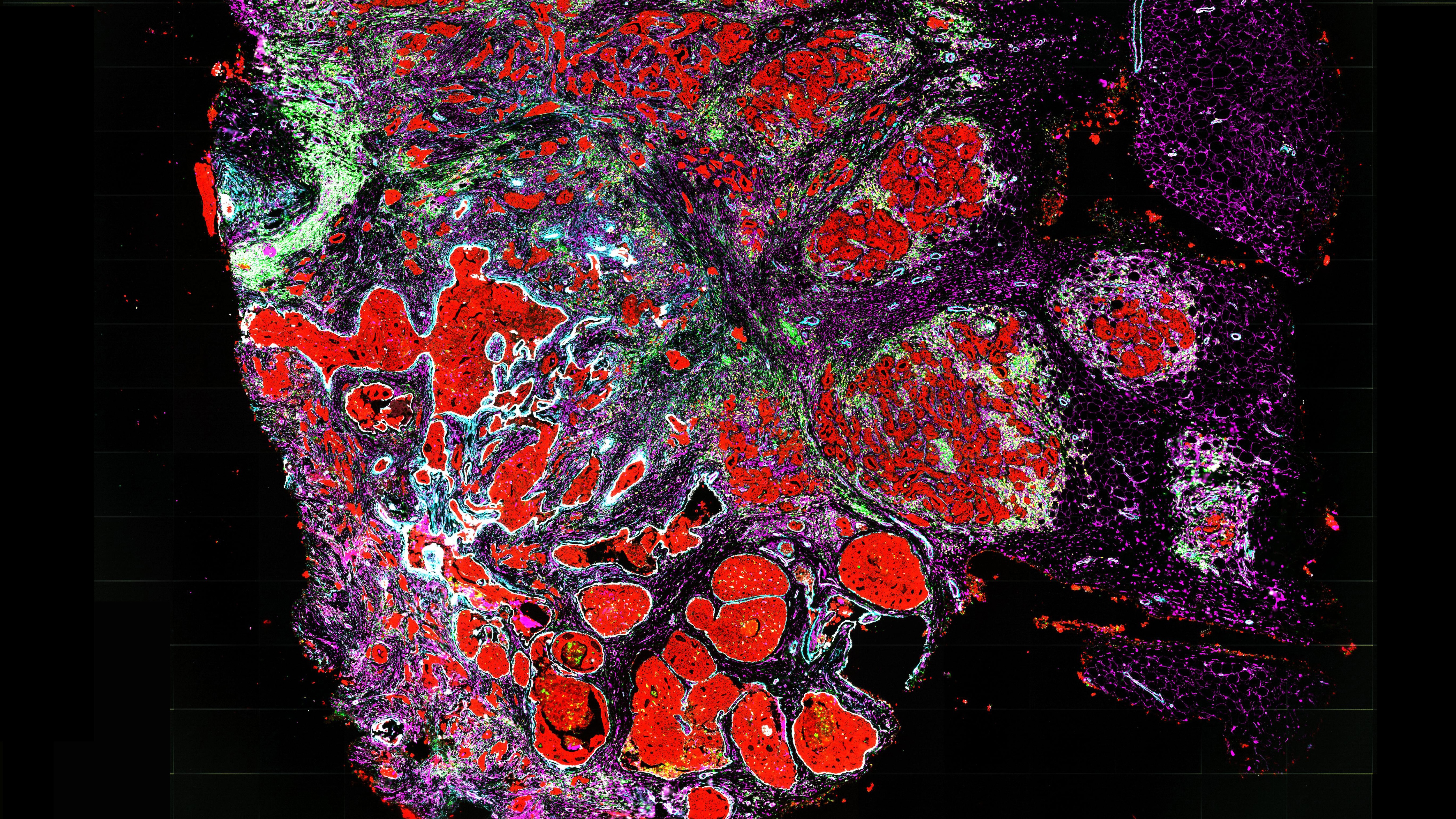

Every tumor is a mix of healthy and abnormal cells, making it difficult to know exactly where and how cancer cells are growing. Now, researchers at Princeton have created a new tool to track the progression of mutations in cancer cells, showing how tumors evolve over time and in space.

“Each tumor is its own ecosystem,” said Ben Raphael, Princeton’s Graduate Class of 1991 Professor of Computer Science and the study’s principal investigator.

While healthy cells typically divide slowly, cancerous cells divide very rapidly and mutate often. Exploiting this key difference, Raphael and Cong Ma, former postdoctoral researcher at Princeton and now an assistant professor at the University of Michigan Medical School, created an algorithmic tool called CalicoST that tracks errors in the genome of cancer cells.

These errors in the genome are introduced during the process of cell division — and result in groups of cancer cells that share distinct mutations, leaving a footprint of the past growth of the tumor. While other technologies have identified mutations in individual cancer cells, Raphael and Ma leveraged a new technology called spatial transcriptomics to also determine the physical locations of these cancer cells within a tumor.

By combining information on which cells are cancerous, how the cancer cells are related to each other by patterns of shared mutations, and where each cell is located in the tumor, the researchers can build an accurate map of how a tumor is growing.

“We’re able to see which regions of the tumor are new and which regions are old,” said Raphael. “The newer regions of the tumor have additional mutations that distinguish them from the older regions.” From this, Raphael said, researchers can infer how the genomes of cancer cells are evolving and where the tumor is growing.

The algorithm, published Oct. 30 in Nature Methods, is one computational tool used in a larger study of over 100 tumors published in Nature and also coauthored by Raphael. Both studies are part of a suite of research from the National Cancer Institute’s Human Tumor Atlas Network, a landmark initiative to construct 3D atlases of human cancers as they evolve.

Understanding how a tumor grows could lead to new methods for treatment, according to Raphael.

“We’ve known for a while that the microenvironment of a tumor is important for treating the tumor,” said Raphael. Whether a tumor is located near the blood supply, for example, can have a significant effect on how it grows and how doctors treat it.

Now, Raphael said, this information could be available in finer detail — after a biopsy, a doctor could know which groups of cancer cells are located next to blood cells or immune cells — making new precision treatments possible.

The article, “Inferring allele-specific copy number aberrations and tumor phylogeography from spatially resolved transcriptomics,” was published Oct. 30 in Nature Methods. Besides Raphael and Ma, authors include Metin Balaban, Michael J. Wilson and Christopher H. Sun of Princeton, and Li Ding, Jingxian Liu and Siqi Chen of Washington University in St. Louis. The research was supported by the Informatics Technology for Cancer Research Program at the National Cancer Institute.