This article is from the Bioengineering: Unlocking mysteries, enabling impact issue of EQuad News magazine.

By Molly Sharlach

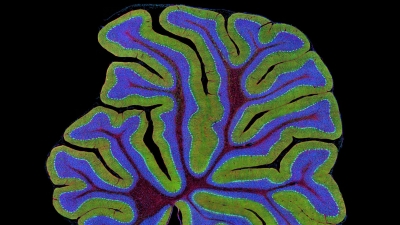

To examine the body’s tapestry of cells, scientists have historically mounted thin sections of tissue on microscope slides, zooming in to study muscles and neurons and identify the hallmarks of disease.

Recent decades have brought revolutions in high-throughput sequencing that allow researchers to measure not only the genome of a biological sample, but also the set of genes that are active in the tissue at a given point in time. And with further advances, this gene activity can now be localized to small clusters of cells — generating remarkable volumes of data that present new computational challenges.

Ben Raphael has made it his mission to create new ways of understanding these reams of data. A professor of computer science who has long specialized in cancer genomics, Raphael has become an expert interpreter of experiments that sequence the genes expressed in a tissue sample while retaining spatial information.

“Biology happens in physical space,” said Raphael. But until recently, high-throughput sequencing required researchers to grind up tissues into thousands of separated cells. “It’s strange that in genomics we have long been ignoring space.”

Now, researchers can preserve spatial information, which can show in unprecedented detail, for example, the locations of tumor cells in relation to connective tissue, blood vessels, and immune cells — which could potentially guide decisions like whether to pursue immunotherapy treatment for a patient with cancer, said Raphael.

As cells divide and move over time, the technology can also keep track of cells’ origins and illuminate the dynamics of cancer, as well as the development of healthy tissues. Raphael’s research group is collaborating with Michelle Chan, assistant professor of molecular biology and genomics at Princeton, to establish methods to trace cellular lineages in animal development.

In another collaboration supported by the Princeton Branch of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Raphael’s team is working with Joshua Rabinowitz, a professor of chemistry and genomics, to quantify metabolite levels in the liver’s various cells. Raphael’s group is using data from the Rabinowitz lab to create topographic-like maps of the liver, showing the gradients of certain carbohydrates or fat molecules over the organ’s maze of veins and lobules.

“We’re interested in all the interactions happening between cancer cells and normal cells that are either supporting the cancer’s growth or suppressing it,” said Raphael. “Being able to look in the spatial context where interactions occur is a great new dimension.”

This article is from the Bioengineering: Unlocking mysteries, enabling impact issue of EQuad News magazine.